Limestone footstool, Cypriot, 1st half of 5th century B.C.

Sculpture in low relief is both real––in the sense of its actual three dimensionality––and illusionistic, in that it shows us forms that are abbreviated, and asks us to imagine them in the round. In this way it stands between painting and sculpture, which is likely why it has fascinated me for so many years. On my most recent trip to the Met, I decided to find various examples of low relief, from different countries and different periods of time. The footstool above has simple decorative elements, slightly raised and incised, their floral pattern contrasting strongly with the violent scene between them.

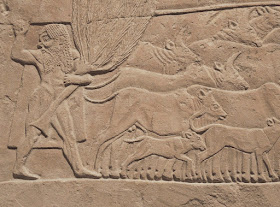

Limestone relief, Cypriot, end of 6th century B.C.

The herdsman Eurytion, carrying a tree as a weapon, moves his cattle forward. Their forms are barely indicated yet are full of life. Although the animals are shown overlapping, moving back in space, their hooves march along all together in a line.

Marble stele (grave marker) of Eukleia, Greek, 4th century B.C.

Some reliefs are very simple: the rounded form of a loutrophoros, a vase to carry water....

Upper part of the marble stele of Kallidemos, detail, Greek, ca. 350-325 B.C.

....or the decorative element of a rosette, clearly geometric in its parts.

Front of a coffin platform, China, 6th - early 7th century.

A beautifully modeled winged horse prances within a roundel.

Marble panel with Two Griffins Drinking from a Cup, South Italian, 800-900.

Two facing griffins are flatly modeled, and are decorated with pattern in the symmetrical design. Its structure is explained by its probable derivation from Near Eastern textile design.

Marble panel with a Griffin, Byzantine, 1250 - 1300.

Here is another griffin made several hundred years later, but still richly patterned, surrounded by floral motifs. It's interesting to compare the way the griffins are carved with the Chinese horse, which is so much more rounded.

Ivory Icon with Christ Pantokrator, Byzantine, 1000-1200.

In this small icon, a great deal of detail and a grand sense of presence is achieved in a very shallow space; clothing, hair, and book are simplified into patterns, while the stern visage of Christ adds the spiritual.

Door Panel, French, ca. 1520-40; oak

Returning to animals, this beautifully carved door has a representation of a salamander, the letter "F" and a crown, all emblems of King François I.

I love the elegance of the rounded tail, the raised bumps along the spine, the haunches and the toes; the clarity and description of form are a marvel.

Fragment with the head of a goddess, Egypt, ca. 2353-2152 B.C.

I'm ending this post with a detail of an Egyptian relief, a tender and lyrical depiction of an ear. It is Egyptian relief carving that is my greatest love in this medium; seeing a great show of Middle Kingdom art, which I wrote about here, inspired me to begin my attempts at clay reliefs. It is wonderful to be able to wander through the Met and remind myself of all the approaches to, and possibilities of, this aspect of art making.

Thank you for providing a steady input of delightful and thought-provoking art - your own included. I too am a lover of bas relief and have very much enjoyed looking at examples in museums in various countries. In the early days of my working in London the British Museum was usually much quieter than now, and I could spend many a lunch hour calmly marvelling.

ReplyDeleteYour blog gives me much pleasure, even though I most often have nothing of substance to remark. Thank you.

Thank you so much for your kind comment, Olga. And I'm glad that you too love bas relief.

DeleteGREAT ideas for dies for pressing Scotts' shortbread.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reminding us of the beauty around us.

Oblique-light brings out surprises sometimes.

Yes, the rosettes are perfect for shortbread.

DeleteYou are very welcome.