From Sea Urchins, 1954

There is so much life on this earth that we humans are hardly aware of; it is too small, or out of sight on high mountains or under the sea, or simply unnoticed. I have a favorite Henry David Thoreau quote:

Many an object is not seen, though it falls within the range of our visual ray, because it does not come within the range of our intellectual ray, i.e., we are not looking for it. So, in the largest sense, we find only the world we look for.Happily, there are people of great curiosity and vision who help us expand our known worlds through their large intellectual ray, such as the scientist filmmaker Jean Painlevé (1902-1989). Over a period of decades, from the 1920s to the 1980s, he made more than 200 scientific films, and is best known for his short films on sea life. I have to thank the artist Michael Brennan for alerting me to this artist, for I have to call him an artist along with a scientist: it is very clear that the aesthetic quality of his work was supremely important to him. It is the aesthetic quality of his films, the visual inventiveness, the sheer beauty, the marvelous scores, from classical to jazz to modern, that makes them special to me.

Sea Urchins

I remember sitting in an elementary school classroom watching film strips or short educational films, but I'm sure we never saw anything as gorgeous as those of Painlevé. Even when he is the scientist––his films are full of complex and detailed information. I should also warn potential viewers that some of them show dissections––and shows us the insides of a sea urchin, it is a beautiful object, mysteriously dangling in a dark space.

From Hyas and Stenorhynchus: marine crustaceans, 1927

A selection of Painlevé's films, some made with his partner Genevieve Hamon, are available from Netflix, published by The Criterion Collection in a set called "Science is Fiction" (you can see a clip from The Love Life of the Octopus at the link). In the film above, tiny crustaceans, only an inch and a half long and decorated with algae, dance to the music of Chopin.

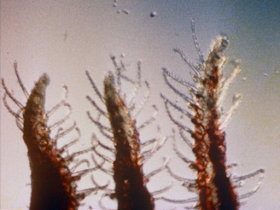

From How Some Jellyfish are Born, 1950

To film these tiny creatures, only 1-2 mm long (that's less than a tenth of an inch!) some seaweed was placed in a very small aquarium, with the camera magnifying them.

How Some Jellyfish are Born

We see so much more than with the eye....and who discovered these animals, and how?...We can see those bulbous extremities, which turn out to have hundreds of poisonous cells to paralyze their even tinier victims/food source. As the tentacles wave about in the film, all I can see is loveliness, but life is not so simple.

Two stills from Sea Ballerinas (Brittle Stars and Feather Stars), 1956

Sea Ballerinas (Brittle Stars and Feather Stars)

The feathered tiny stalks on the arms of the Feather stars are for breathing and for gathering microscopic food particles. We are told that "They look like strange incantations in motion". There are many moments of visual and verbal poetry in these films.

Sea Ballerinas (Brittle Stars and Feather Stars)

There's also a lot of humor. Painlevé presents us with the conductor Galathea, a species of squat lobster, who sure looks like he's conducting this floating feather of a star fish.

From The Sea Horse, 1933

One of the most wondrous creatures to inhabit our planet is this fish....yes, it's a fish....whose upper body is the shape of a horse. I wonder how this evolutionary quirk happened.

The Sea Horse

It turns out that the most fascinating fact about this fish is not its shape, but its reproductive strategy. It is the male of the species, seen above, that gestates the young in a pouch in his body; the female deposits her eggs there, he fertilizes them and carries them until birth. In the screen shot above, he is in labor, and you can see the tiny seahorses that have emerged from his pouch. This little animal shows us that gender roles don't have to be fixed as we humans know them.

From The Vampire, 1945

This brief 9 minute film shocked me; it was so different in tone from all the others I'd watched: it began with "strange and terrifying" creatures, diseases spread by insects, and some scenes from Murnau's film Nosferatu; the inspiration for the vampire coming from animals in nature. Creepy creepy creepy. Then we're introduced to the South American vampire bat. Horrifying. It wasn't until I read the interesting essay by Scott McDonald on the Criterion site that I learned the film, made just after the war, was a political statement, expressing a hatred of the Nazis; Painlevé had to spend years in hiding during the occupation of France.

From Acera, Or The Witches' Dance, 1972

These short films are mostly about wonder, and beauty, and for me the most lusciously gorgeous of all was Acera, about a small sea mollusk. These rounded creatures are dramatically organic forms in a dark universe.

Acera, Or The Witches' Dance

The become monumental.

Acera, Or The Witches' Dance

They are also the most elegantly lovely dancers as they float; a "fold of skin forms a cloak around its body, allowing it to move and swim". Delightful lilting music accompanies the buoyant dancers, who bound up and float down to attract a mate. You can't imagine from a still image how wonderful these mollusks are, how beautifully they are filmed; it is a project of sheer joy. And a project to show that sexuality isn't fixed, since these creatures can be male or female, or both at the same time. Life is a wonder, and much richer and more varied than we imagine.